Save Dhaka's Rickshaws

Dhaka's Rickshaws Under Threat:

Stop the World Bank's War on the Poor

Press Release: Campaigners Achieve a Victory in Effort to Save Dhaka's Rickshaws (March 2, 2005)

UPDATE - FEB. 7: On Feb. 1, Dhaka newspapers announced that a US$4.5 million "rehabilitation programme" was being introduced to retrain rickshaw drivers for other professions. Local NGO leaders are skeptical that the money will trickle down to those in need. At the same time, the real issue goes unaddressed: Why ban rickshaws in the first place? In fact, the "rehab" initiatives have been introduced along with a more vigorous pursuit of the rickshaw ban policy. One more road, stretching from the Science Laboratory to the National Press Club via Shahbag, is to be made off limits to non-motorised vehicles in February. Part of that stretch has already been closed. ITDP filed a formal complaint through the World Bank's own channels, and in the absence of a response, will go public with the letter after Feb. 28. The international campaign is on hold until then, although protests in Dhaka will continue. Please check back with this page in early March.

UPDATE - JAN. 12: In response to the most recent rickshaw ban in Dhaka, which went into effect on Dec. 17 on Mirpur Road, World Carfree Network released an Action Alert. Big thanks to the hundreds of people who sent letters to World Bank and other officials. The Dec. 6 Action Alert expired on Dec. 31, and the effect of this and local Dhaka actions are now being assessed. A formal complaint is also being filed through the World Bank's official process.

In Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, most journeys are made on foot, and bicycle rickshaws are the main form of vehicular transport. Rickshaws are an efficient, non-polluting way to move around, and for many people without job skills, pulling a rickshaw is the only option other than begging or crime. It is estimated that five million people in Bangladesh are dependent on the income of rickshaw pullers for their survival. In Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, most journeys are made on foot, and bicycle rickshaws are the main form of vehicular transport. Rickshaws are an efficient, non-polluting way to move around, and for many people without job skills, pulling a rickshaw is the only option other than begging or crime. It is estimated that five million people in Bangladesh are dependent on the income of rickshaw pullers for their survival.

While rickshaws, or bicycle taxis, have been introduced successfully in Western cities such as New York and Berlin, the World Bank has shown nothing but hostility towards rickshaws being the dominant mode of vehicular transport in Dhaka, seeing them as an impediment to their idea of development (e.g., mass motorisation, fossil fuel dependence, traffic jams, dirty air, and accelerated climate change).

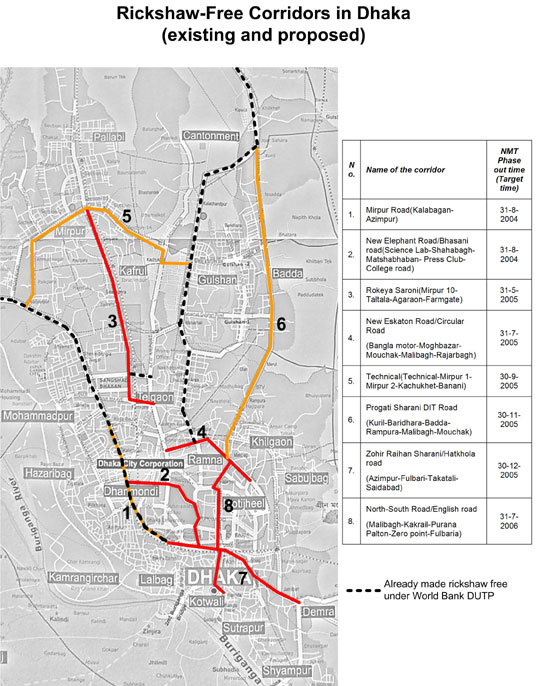

Under pressure from the World Bank, Dhaka City Corporation (The City of Dhaka) announced that from December 17 it plans to ban rickshaws and non-motorised transport from an important road in Dhaka - Mirpur Road from Russell Square to Azimpur. This is part of the World Bank-funded Dhaka Urban Transport Project, which has run since 1999 and is now coming to a close. But this initial ban is just the test case in a much larger World Bank plan that would eliminate rickshaws from eight major roads (120 km) in this city of ten million people. Pushing rickshaws off the main roads would allow motor vehicles to become the dominant mode of vehicular transport in the city. At the same time, the World Bank is pressuring the Bangladeshi government to pass a law freeing the bank of legal liability for any harm that results from its policies.

Increasing limitations on rickshaws in Dhaka are causing untold hardship to the poorest and most vulnerable segments of society, reducing the mobility of the middle class (particularly women, children, and the elderly), and contributing to air pollution and motorisation. Meanwhile, roads that have completely banned non-motorised transport are still some of the worst affected by traffic jams. Increasing limitations on rickshaws in Dhaka are causing untold hardship to the poorest and most vulnerable segments of society, reducing the mobility of the middle class (particularly women, children, and the elderly), and contributing to air pollution and motorisation. Meanwhile, roads that have completely banned non-motorised transport are still some of the worst affected by traffic jams.

World Carfree Network, concerned organisations in Bangladesh and around the world, and Dhaka's many rickshaw unions are all prepared for action to save the rickshaws. If the most vulnerable members of the population are to go hungry, it will not happen without a fight. Banning rickshaws and building highways while people face starvation is nothing short of a war on the poor.

Important Points:

- Rickshaws are in many ways the ideal form of transport: they provide door-to-door transport at all hours and in all weather, emit no fumes, create no noise pollution, use no fossil fuels, and employ large numbers of the poorest people.

- It is not the rickshaws that are clogging the streets; it's the cars. In 1998, the less than 9% of vehicular transport by car required over 34% of road space, while the 54% travelling by rickshaw took up only 38% of road space. The solution is not to reduce rickshaw transport, but to prevent the growth of car use, by minimising the road space and parking space allocated to cars.

- In addition, there are many simple solutions that could benefit both the rickshaw-riding majority and the car-owning minority. Instead of banning rickshaws, the World Bank and local authorities could be (a.) providing dedicated lanes and cycle rickshaw stations that would prevent conflicts between modes, (b.) implementing a programme to help improve the quality of the rickshaws, (c.) supporting cycle rickshaw drivers with training, uniforms, tariff standardisation, etc., (d.) creating cycle lanes throughout the city, and (e.) supporting public transit through bus-only lanes, bus-only turns, etc.

- Many rickshaw pullers fled from starvation in the villages. With exceptionally bad floods this year, many villages lack sufficient food and seeds. Cutting back on rickshaw income means directly attacking the ability of the poorest and most vulnerable to survive - not just the rickshaw pullers themselves, but the families and entire villages that they support.

- The Mirpur Road is a disastrous choice for a rickshaw ban, as there are no alternate roads for rickshaws, and it is extremely difficult to walk on this road because of the prevalence of street vendors.

- Accommodating the automobile over other modes is undemocratic, supporting a wealthy elite while the majority suffers. In the long run, even the rich will not benefit from rickshaw bans, as current policies will lead to more traffic jams, dirtier air and increased noise pollution.

- The World Bank figure that the rickshaw ban will cover "only 6% of roads" is highly misleading. Maybe 6% of roads, but those corridors carry well over 50% of all the traffic in the city. Further, the figure of 6% is misleading because Dhaka has only a small number of arterial roads which due to the lack of a secondary road network means must carry all kinds of traffic, including short trips by pedestrians and rickshaws as well as longer trips by motor vehicles. The proposed restrictions cover almost all the main arterials (the widest roads in Dhaka), and almost all of the north-south corridors, where a large percentage of the overall traffic occurs. The rickshaw-ban roads are almost all in the range of 25 metres to 45 metres wide (including walkways), i.e., at least three lanes in each direction. Some are even wider. So the World Bank's claim that traffic cannot be segregated on the arterial roads is simply false.

- World Bank policy in Dhaka is inconsistent with the spirit of the World Bank's urban transport strategy, Cities on the Move (2001), which is highly progressive and supportive of non-motorised transport.

- Rickshaws are the main source of vehicular transport for the middle class. Since there are often not alternatives within their means, a rickshaw ban is a restriction of their freedom of movement, and therefore a violation of Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- While proposing for further rickshaw bans between Russell Square and Azimpur, the Dhaka Transport Coordination Board presented data showing an increase in average motor vehicle speeds (15 kmh to 24 kmh) in other parts of the same corridor where a rickshaw ban has already been imposed. But did they analyse how robust and stable the gain in speed reductions would be? Considering experiences of the other rickshaw-free roads, is it not more likely that the gain in speed would be very short lived and the extra space created would soon be filled by more motorised vehicles? And further, wouldn't a ban on motor vehicles on major roads similarly speed up the rickshaws and also allow space for bicycles and pedestrians?

Further Information:

- Newspaper article, New Age Metro, Dhaka, Nov. 24, 2004: "No Rickshaws from Russell Square to Azimpur by December"

- Newspaper article, The Daily Star, Dhaka, Aug. 2, 2004: "Dilemma Delays Plan for Fresh Ban on Rickshaws"

- World Bank statement, Dec. 19, 2001, expressing the need for rickshaws to be banned on major roads in Dhaka: "Laying of the Foundation of Mohakhali Flyover" (Rickshaws, not cars, are seen as clogging the streets.)

- World Bank document, undated, very positive toward non-motorised transport: "Poverty Reduction and Social Assessments" ("Transport interventions that promote the use of NMT usually contribute directly to the welfare of those people who cannot afford motorised transport. NMT is, many times, also the most appropriate and efficient form of transport.")

- World Bank document, July 2003: "Transport and Climate Change: Priorities for World Bank-GEF Projects" ("Preserve and Expand NMT Options. Motorised transport development and safety concerns often reduce existing NMT usage. Low capital investment requirements make bike and pedestrian transport accessible to low income groups.")

- World Bank document, April 1994: "Non-Motorized Transport: Confronting Poverty Through Affordable Mobility"

- Dhaka Urban Transport Project (1999-2005), funded by the World Bank. The Mirpur Road rickshaw ban is a component of this project.

- Newspaper article, New Age Metro, Dhaka, June 25, 2004: "[World Bank] Team to Review DUTP Progress" (General incompetence delays progress on Dhaka Urban Transport Project.) Similar article in The Daily Star: "DUTP Gets More Time"

- The government has not released updated information on the transport situation in Dhaka. From old statistics and estimates in annual increases, we estimate that only up to 17% of vehicular trips in Dhaka are made by private car, while rickshaws account for approximately 50% of vehicular travel. (Most trips are made by foot.)

- Cycling would be a good option for the poor, but current conditions are quite dangerous and unpleasant, with mostly low-income workers such as guards and garment factory workers using this mode. For most of the poor, the only option is to walk, which is made difficult by extremely poor conditions for pedestrians (sidewalks blocked by parked cars, construction supplies, large trash bins, etc.; lack of signals for street crossings, and the noise and fumes of the motorised transport).

- Rather than seek to improve conditions for the over 80% who do not travel by car, policies to date have been focused exclusively on motorised transport, especially taxis and private cars. New projects include the recent construction of the Mohakhali Flyover (pushed for and financed by the World Bank, at a publicised cost of US$19 million), which has had no discernible effect other than to relocate, and possibly increase, the size of traffic jams in that area.

- While transport authorities like to say that it is not their job to be concerned about employment for the poor, it is unclear who is expected to take on this responsibility. A traffic policewoman told us that she disagrees with the government policy, as she is sure that it will increase crime in the streets. It is not, after all, reasonable to expect people in a very poor country, with no other employment options, simply to return to their villages and starve to death quietly. If their employment were endangering the health or security of others, one would wish to seek alternatives; given that their employment is providing high-quality service to a large portion of the population with no negative consequences to our environment - far more than can be said of cars or even buses - the policy of encouraging a reduction in rickshaw use is simply criminal.

- The World Bank also supported the closure of Adamjee Jute Mills, the largest jute mills in the world, which put 25,000 people out of work. According to the website of War on Want, the reasons for the closure were "corrupt officials, mismanagement and bureaucracy."

Map:

Contacts:

- Roads for People, Dhaka (an alliance of NGOs in Bangladesh supporting non-motorised and public transport - Roads4People@yahoo.com)

- ITDP, New York City (promotes sustainable transport in Bangladesh and worldwide)

- World Carfree Network, Prague

|

![[Home]](http://www.worldcarfree.net/img/logo1.jpg)

![[Home]](http://www.worldcarfree.net/img/logo1.jpg)